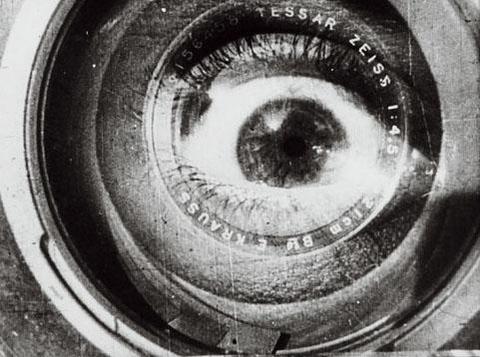

The male

gaze refers to the identification of the male spectator with the camera, as it

observes a female. In narrative cinema, it is men who are active, and women who

are passive. As Mulvey points out in “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema,” “the

determining male gaze projects its phantasy on to the female figure which is styled

accordingly” (Mulvey 837). Within traditional narrative cinema, men as

protagonists have agency. As such, the apparatus follows them, and sees as they

see. What they see, of course, is woman – “a sexual object…[an] erotic spectacle”

(Mulvey 837) who exists within the film for the sole purpose of being looked at. According

to Mulvey, that the male gaze focuses on the female reflects the “heterosexual

division of labor” and therefore avoids the man, “his exhibitionist like”

( Mulvey 838). The spectator adopts the gaze of the camera, and therefore of the man,

and thereby comes to see the woman as nothing more than a thing to be consumed.

Consider, for example, an early scene in Hitchcock’s Rear Window, a

film discussed briefly in Mulvey’s “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema.” In

this scene, the camera shows us the world as the main character, a man, sees

it. The camera (that is, the man, and by extension, the spectator) observes his

neighbors while on the phone, pausing to leer at a scantily clad woman who

dances, unaware of his attention, in her kitchen. The gaze is then shifted to another

mostly undressed woman, this one presumably married, as she lies in bed arguing

with her husband, whose relatively brief screen time underscores the prevalence

of women as objects to be looked at. These shots of the neighboring women are

interspersed with shots of the protagonist himself, reinforcing the spectator’s

manhood. Throughout this scene, the man speaks on the phone about business,

which places the man in a position of power, from which he can take action. The

women he sees are on display, and are only there for his, and for the spectator’s,

pleasure.

The male gaze is not limited to

film. Chapter 3 of John Berger’s Ways of

Seeing describes the European tradition of nude paintings. Like in cinema,

women in the European nude are passive, and exist only to be looked at. In

these paintings, it is implied that “the subject (a woman) is aware of being

seen by a spectator” (Berger 49). This spectator is “presumed to be a man.

Everything is addressed to him. Everything must appear to be the result of his

being there” (Berger 54). The gaze of this spectator and the gaze of the camera

are one and the same. They are inherently male, and actively look upon a woman

who has no agency of her own.

The oppositional gaze, as

described by Bell Hooks, refers to a different kind of spectatorship. The

oppositional gaze is unable to accord with the white, heteronormative male gaze

described by Mulvey. It is the gaze of the socially oppressed black woman,

which resists and criticizes the perspective offered by traditional narrative

cinema. It emerges, as Hooks writes, “experientially…one learns to look a

certain way in order to resist” (Hooks 116). This gaze emerges through the

efforts of black female spectators to interact with a cinema that “perpetuates

white supremacy and with it a phallocentric spectatorship where the woman to be

looked at and desired is ‘white’” (Hooks 118). For Hooks personally, this gaze first

looked when watching Sapphire, a black female character from the series Amos n’ Andy. Hooks explains that the

oppositional gaze of the black female spectator must be incorporated into

feminist film theory because black women “actively choose not to identify with

the film’s imaginary subject because such identification was disenabling” (Hooks

122).

Like for many people, reading “Visual

Pleasure and Narrative Cinema” and Ways

of Seeing irrevocable changed the way that I perceived the portrayal of

women in many forms of media, especially film. I can no longer watch a film without

instinctively watching, and waiting, for sexist Hollywood conventions. The

instinctive, automatic adaptation of the role of male spectator is very

difficult for me to achieve. I continue to be active when I watch films, but

rather than emulating the possessive agency of the male gaze, I lean more

towards something like the oppositional gaze described by Hooks. I am more removed

and critical, and I resist the inherent oppression of film conventions,

although I may suffer from it less than others. I won’t claim that since

reading Mulvey I have never seen as I once did, or that I never will again. But I

catch myself more often than not, and I work to find a new way of looking – my own.

Berger, John.

"3." Ways of Seeing.

London: British Broadcasting, 1973. 45-64.

No comments:

Post a Comment